Hunt for chubby book thief

The Henley Standard published this bit of info about a book theft:

THREE rare books have been stolen from Jonkers in Henley.

The most valuable was The Man Upstairs by PG Wodehouse, published in 1914, which is worth £2,750. The others were Time For A Tiger by Anthony Burgess, published in 1956, worth £800, and Dead Mr Nixon by TH White, published in 1931, worth £500.

All three are first edition hardback copies and are clothbound. They were stolen from the rare book specialists in Hart Street on June 8.

Police said the thief entered the shop at about 2pm and asked to see different books but then left abruptly when the assistant was occupied.

On July 7, the shop was contacted by an antiquarian bookseller in New York which was offered TH White’s murder mystery but turned it down. A stock check by staff at Jonkers found that the other two texts were missing.

Christiaan Jonkers, who owns the shop, said it would be difficult for the books to be moved on unnoticed.

He said: “Whoever stole them will be ultimately disappointed because they are so recognizable. The antiquarian book world is so tight-knit that as soon as they try and offer them for sale somebody will pick up on them.

“There are not many copies of these books, hence their value.”

The thief is described as being in his fifties, of average height and chubby.

Robert Bruce Cotton, 1571-1631 - Book Collector

Sir Robert Bruce Cotton is known as a distinguished bibliophile and amassed one of the most important libraries of his time. He was known as librarian, record-keeper, one of the founders of modern government and rule by precedence and common-law.

Sir Robert Bruce Cotton is known as a distinguished bibliophile and amassed one of the most important libraries of his time. He was known as librarian, record-keeper, one of the founders of modern government and rule by precedence and common-law.

His 1000-book library significantly changes history. [image]

Son of Thomas Cotton of Huntingdonshire (original family name was probably de Cotun). Family had profited well by the dissolution of the monasteries and by marriage. They were neighbors and `kinsmen' of the Huntingdonshire Montagus (that is, the Duke of Manchester), and distant relatives of Robert the Bruce of Scotland (original family name was probably de Bruis, de Broix, de Brois, etc).

Entered Jesus College, Cambridge, in 1581 and received his BA in 1585. Had begun `antiquarian studies' under William Camden at Westminster School before going to Cambridge. He began collecting notes on the history of Huntingdonshire county when he was seventeen and never stopped collecting information, specifically old government documents. His collection of records surpassed that of the government. He effectively established the first public law library, open government `public records', and what we might call today a scholarly `think-tank'. The DNB puts it thus: the library of Cotton House became the meeting-place of all the scholars of the country.

C.J. Wright, of the British Library, puts it as follows:

"The Library of Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631) is arguably the most important collection of manuscripts ever assembled in Britain by a private individual. Amongst its many treasures are the Lindisfarne Gospels, two of the contemporary exemplifications of Magna Carta and the only surviving manuscript of `Beowulf'. Early on in his career, Cotton had advocated the foundation of a national library of which his collection would form a part... he was always generous in the loans he made other scholars.

... the Restoration and the revival of a political culture in which disputes were solved by precedent rather than violence placed the Cottonian library again at the centre of the overlapping circles of scholarship and politics." (SRCC)

In 1590 joined the Antiquarian Society (renewing contact with Camden) and presented a number of papers based on old manuscripts. He also collected Roman monuments, coins, fossils, etc. At the end of the reign of Elizabeth, the Society was meeting at Cotton's house and his collection of manuscripts had gained fame within the Society. In 1600 the queen's advisors contacted him on a question of official protocol with respect to Spanish ambassadors. He assisted Camden in preparing Camden's Britannia. Francis Bacon and Ben Johnson often used his library.

When king James arrived from Scotland, he knighted Cotton in 1603 and called him `cousin' (after which Cotton always signed his name Robert Cotton Bruceus). He became a favorite of James, represented Huntingdon in Parliament, drew up a pedigree (family tree) of James, wrote a history of Henry III, and wrote tracts such as `An Answer to such motives as were offered by certain military men to Prince Henry to incite him to affect arms more than peace.' In 1608 he investigated abuses within the Navy, and was invited to attend the Privy Council (this was important since this was really the ruling body of England, no doubt his role was that of an `expert witness').

King James seems to have consulted with him on schemes for increasing government revenue, and he wrote a survey of the various mechanisms by which previous Kings had raised money. He strongly supported (if not invented) raising money by establishing a new feudal rank, the baronet (this was a new `feudal' rank below that of baron; essentially you could just buy it if you had the money. This was widely used (not that different from political fund-raising today)).

Collaborated on Speed's History of England and Camden's History of Elizabeth, perhaps to the point where he should be credited (Francis Bacon considered him the author of History of Elizabeth; when Camden died he willed much of his material to Cotton). King James wanted him to write a history of the Church of England, but Cotton provided all the material to Archbishop Ussher. When Sir Walter Raleigh was imprisoned in the Tower, he borrowed manuscripts from Cotton. Francis Bacon wrote the Life of Henry VII in Cotton's library.

People were beginning to fear Cotton's library. The DNB puts it thus:

"A feeling was taking shape... that there was danger to the state in the absorption into private hands of so large a collection of official documents as Cotton was acquiring. In 1614... a friend, Arthur Agard, keeper of the public records, died, leaving his private collection of manuscripts to Cotton. Strong representations were made against allowing Cotton to exercise any influence in filling up the vacant post. The Record Office was injured, it was argued in many quarters, by Cotton's `having such things as he hath cunningly scraped together.' In the following year damning proof was given of the evil uses to which Cotton's palaeographical knowledge could be put. ..." (DNB)

He was involved in dealing with the Spanish ambassador on behalf of Somerset, an enemy of Buckingham. He confessed everything and spent eight months imprisoned without a trial, after which he was pardoned. He was then employed searching Sir Edward Coke's library.

The DNB provides a feel for the interaction of his library and politics:

"... Cotton ... was studying the records of the past in order to arrive at definite conclusions respecting those powers of parliament which the king was already disputing.... In 1621 he wrote a tract to show that kings must consult their council and parliament `of marriage, peace, and warre'. ...

Cotton appeared in the House of Commons for the third time as member for Old Sarum... and was returned (ed, as representative to Parliament in 1625). Here he first made open profession of his new political faith. ... Eliot's friends made a determined stand against the government, then practically in the hands of Buckingham. ... (ed, Cotton did not speak in the debate) but ... handed to Eliot an elaborate series of notes on the working of the constitution. The paper was circulated in the house in manuscript...

In September 1626 he protested, in behalf of the London merchants, against the proposed debasement of the coinage, and his arguments, which he wrote out in A Discourse touching Alteration of Coyne chiefly led to the abandonment of the vicious scheme. ... he drew up an elaborate account of the law offices existing in Elizabeth's reign... the (Privy) council invited his opinion on the question of summoning a new parliament, and he strongly recommended that course... In 1628 he published a review of the political situation ... The Dangers wherein the Kingdom now standeth, and the Remedye, where he drew attention to the ... sacred obligation of the king to put his trust in parliaments. (ed, in 1628) the opposition leaders Eliot, Wentworth, Pym, Selden, and Sir E. Coke, met at Cotton's house to formulate their policy. In parliament Cotton was appointed chairman of the committee on disputed elections..." DNB

After this, Cotton was an enemy of the king, and was destroyed. Essentially, Cotton was framed on charges of `treason', and the library seized by Charles I (on the instigation of Buckingham). Cotton died of a broken heart, but everyone understood that the library had been seized for political reasons. Upon the Restoration, Cotton's `national library' was restored, pretty much along the lines of Cotton's original vision.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A particularly good overview of Robert Cotton and the historical impact of his library is Sir Robert Cotton, 1586-1631: History and Politics in Early Modern England, by Keven Sharpe (Oxford U. Press). The following is an extended extract that I hope well serves Sharpe's material:

"To understand how Cotton used his own library, we must investigate how he bound, stored, and catalogued his books. ... Cotton viewed his library as a working collection and adopted an arrangement that was utilitarian rather than bibliographically correct by modern standards... Things were bound together that were consulted together....

... the library was arranged under the famous busts of the emperors of Rome (ed. Cotton's library was about 26 feet by 6 feet. Each bookcase had a Roman Emperor on top, and thus books were cataloged by Emperor. Sharpe provides a diagram of the layout of the library.)

... in the absence of a catalogue ... Cotton's knowledge of the library's contents was all the more important. ... he knew the contents and the use of his own books very well. ... The full description required by the Privy Council when it ordered a catalogue (ed. from Cotton, which he provided), suggests how well, in the absence of such an index, Cotton knew his manuscripts and books.

... Cotton was assisted by his librarian, Richard James, who, despite D'Ewes's accusation that he sold his master's papers, seems to have served Cotton well. ... if we are to believe .... gossip ... Cotton (also) enjoyed the help of one of his bastard sons.

Why was Cotton's library so important in the intellectual and political history of James I's reign? Apart from the Royal Library, the collections of the Inns of Court and the College of Arms, London libraries were predominantly ecclesiastical. ...

... the library ... seems frequently to have shifted... It was probably not until 1622... that the library was located ... at Westminster, next to the Houses of Parliament. ...

... Several grateful borrowers commented on the freedom with which Cotton allowed all to consult his material. ...

The importance of the collection was not due to its size. With less than a thousand volumes, it did not compete favourably in size with other private libraries of the period. But the Cottonian collection was essentially a library of manuscripts, possessing a monopoly of the most important material for early English history.

But Cotton's loan lists show that many with literary interests wider than the purely historical borrowed...

For lawyers and judges, the library was a storehouse of the case law which it has been argued (with considerable exaggeration) dominated their attitudes. Sir Henry Montagu sought to borrow the civil law collections against Hanse privileges; Coke required abridgments of parliamentary records. ... Cotton's legal friends who were former members of the Society of Antiquaries continued to use ... their colleague's collection...

For those in government positions, the library acted as a state paper office and research institute, providing a better service than the unsatisfactory official collections and repositories in the Tower and Exchequer. Clement Edwards, a clerk of the Privy Council, went to Cotton for the Council books... Henry Montagu , when Lord Treasurer in 1620, used Cotton's collection of notes on ways of increasing royal revenue; ...

The list of those borrowing... reads like a Who's Who of the Jacobean administration: it includes the King and Queen, Attorney Francis Bacon... leading court noblemen often sought deeds to prove claims of land, especially title to property...

... the loan lists yet illustrate clearly the pure quest for knowledge and the breadth of interest of some of those who were active in political life. Such evidence is a firm warning against limiting the outlook of early seventeenth-century men. ... the lawyer's of Cotton's acquaintance continued an interest in history ... William Camden was no mere herald, but a scholar in the widest sense; Bacon's writings were by no means the creation of one who was but the king's solicitor. ...

The strife of court factions seems much more subdued when seen through the world of exchange of books. Neither are there indications of rival cultures of `court' and `country' in the names of those borrowing from Cotton's library. ... Cotton's library, ... as far as the evidence suggests, stayed open to all as a public institution.

Perhaps the very existence of the library as a public collection accounted for its stormy history. Though a storehouse of official papers and arcana imperii, the library was open to all, and the failings of divine monarchs were laid bare to lowly mortals. ... Cotton's library seemed to substantiate criticism of royal policy. The arguments from precedent were won by the antiquaries and lawyers of the House of Commons.

... By 1622, Thomas Wilson, Keeper of the Records, was worried about official papers remaining in Cotton's hands. ...

.... In 1626 Buckingham advised Charles I to close the library...

In 1629 the library was closed by order of the king. ... Charles I thought it time to investigate Cotton's library... The Council ordered that the library be searched by Sir Henry Vane and, ironically, Sir Edward Coke, whose own collection had been scrutinized by Cotton some years earlier.

... (William) Boswell was instructed to supervise the drawing of a catalogue which was commenced with Cotton's assistance. ... the library was never returned to Cotton in his lifetime. ...

... Cotton's friends... understood the partisan nature of the arrests and the closure of the library. Montagu and Arundel defended Cotton against what Arundel openly called the `pretence' of the investigating committee.

... the Privy Seal, the Earl of Manchester (a Montagu, ed.) ... and others, having examined Cotton's library, reported to Charles I the efforts Cotton had expended in building the library and his readiness to serve the king. Manchester was Cotton's kinsman ...

But it was too late: in May 1631 Cotton died ... King Charles sent Manchester to comfort Cotton on his deathbed. ..." Sharpe

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sharpe also provides an interesting look at the politics of the day, involving the Montagu's:

"The Earl of Manchester wrote to Edward Montagu that the examination of his kinsman Cotton `makes a great noise in the country'. ...

No lawyer, Cotton yet possessed a knowledge of the law sufficient for him to be consulted ... on legal questions. ...

It is evident of Cotton's standing in the House of Commons that though he did not sit in the Parliament of 1614, he was consulted on the most important issue. ...

Cotton's assistance was crucial... On 20 May, Sir Edward Montagu and Henry Cotton went with William Hakewill and Sir Roger Owen to research in Cotton's library. ...

(In the Parliament of 1621) ... Both Sir Edward and Sir Henry Montagu sought their kinsman Cotton's advice during the parliament, but the Montagu influence was not exercised, or was exercised unsuccessfully, on his behalf at the hustings.

It is excellent evidence of Cotton's importance that he was again consulted on many of the issues for which that parliament has been remembered. ... " Sharpe

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sidney Montagu (neighbor of Cotton's Conington estate) is on record as promising to return some books. I wonder if he ever did? Wright writes:

"... it seems that Conington Castle may have been a second major repository for the Cottonian collection. ... Camden refers to Cotton's `cabinet' at Huntingdon... He evidently kept state papers and documents at Conington, and may have had books there: Sidney Montagu promised to return borrowed books to Conington..." Wright

Bishop Richard Montague, a library borrower, called Cotton's library a `Magazine of History' (presumably using `magazine' in the sense of a storehouse).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Part of the DNB summary of his work is as follows:

"... His collection of coins and medals was one of the earliest. Very many languages were represented in his library. His rich collection of Saxon charters proved the foundation of the scholarly study of pre-Norman-English history... Original authorities for every period of English history were in his possesion. His reputation was European. ...

Cotton wrote nothing that adequately represented his learning... His English style is readable, although not distinctive, and his power of research was inexhaustible. Only two works, both very short, were printed in his lifetime, The Raigne of Henry III, 1627, and The Dangers wherein the Kingdom now standeth, 1628. ...

Many of his tracts were issued as parliamentary pamphlets at the beginning of the civil wars .... In 1657 James Howell collected fourteen of Cotton's tracts, under the title Cottoni Posthuma. ... Eight papers read by Cotton before the Antiquarian Society are printed in Hearne's Curious Discourses (1771)."

Sir Edward Coke is considered one of the important figures in the history of common law.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A letter from the Inner Temple Library (reproduced in Sharpe), containing Cotton's response to the request for Parliament to use his library in 1614 while he was ill:

"I held it my bownden dutie to that House (to which I owe my service & life) to preferre to their satisfactions before my owne safetye. And for that purpose adventured to my house, that I might recomend unto yor hands (as the principall servant of that bodye) the use of all such collections of parliament as I had (out of my duty to ye publique) taken paines to gather those gatheringes that may properly bee of use this time are sorted together under the title of parliament bookes and had my memorye (now distracted by infirmitye) beene soe ready I could wishe I should have beene able to make that searche shorte which I must now humbly recomend to the labour of such as the house shall leave the charge to. let me I pray you soe far beg of your love and the bounty of the house that Sir Edward Montagu (one amongst them) and Mr Cotton of the Middle Temple my brother may see the deliv[er]y out of such bookes as the House shall require ffor I have been intrusted with most of the mayne passages of state and to suffer those secretts to passe in vulgar may cause much blame to me and little service to the House. Besides let me presume to begg that the labours of my life (wch I am most ready to offer to all publique service) may not be prostitute to private uses. And that only such thinges as concerne the pointe now in question may be extracted and the rest left unto that servant of the house wch hopeth shortly to give his dutiful attendance at their further pleasures." Cotton

[Top]Real-Life Thriller About Rare Book Theft at New York Public Library

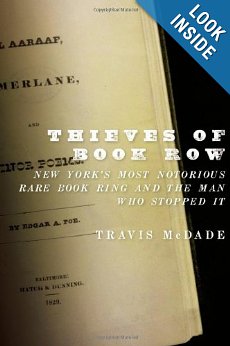

This article is from the News Bureau at the University of Illinois. Permission was given for its reprint here by the author, Phil Ciciora, Business & Law Editor | 217-333-2177; pciciora@illinois.edu . I have looked for a copy of this newly released book and found it primarily in paperback. Amazon.com has a few hardbacks still available as I write this and one listed as "collectible" in the book seller's section new with dust-jacket in a mylar cover.

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new book from a University of Illinois expert in crimes against rare books tells the real-life story of the biggest score in rare-book theft and the dogged hunt for the perpetrators by the special investigator of the New York Public Library.

The book, titled “Thieves of Book Row: New York's Most Notorious Rare Book Ring and the Man Who Stopped It,” was written by Travis McDade, the curator of law rare books at the College of Law. It’s a Depression-era cat-and-mouse thriller about the pursuit of the most successful rare-book ring in U.S. history.

“There have always been thieves stealing from libraries, but this was different,” McDade said. “This was – and probably still is – the all-time worst theft of rare books in the U.S.”

According to the book, which was published by Oxford University Press, the price of rare books in the 1920s, particularly in the “Americana” genre, started to skyrocket, creating a unique opportunity for unscrupulous booksellers and thieves desperate enough to raid libraries.

“It was the boom years of the Jazz Age, and you had the J.P. Morgans, the Andrew Carnegies, the Henry Huntingtons and the like buying rare books to stock in their libraries,” McDade said. “Thanks to this book-buying bubble, all of the public libraries in the Northeast now had books on their shelves that were pretty valuable.”

With the value of first-edition books going through the roof, a ring of thieves on Book Row – a six-block sliver in lower Manhattan about 20 blocks south of the library – conspired to make some money by raiding libraries and then selling the stolen books to rare booksellers, some of whom were willing to turn a blind eye to the dubious provenance of the prized antiquities.

“Naturally, it turned into this big money-making concern that, by the end of the 1920s, was a very sophisticated operation,” McDade said. “By that point, they had the stealing of rare books down to a science. It was almost economies of scale – someone stole the book, another person ‘cleaned’ it to remove any identifying marks of ownership, and then someone else sold it. And the way they fenced them was through the antiquarian bookshops on Book Row.”

The New York Public Library had a special investigator, G. William Bergquist, whose job was to prevent these types of crimes from happening – or, if they occurred, to track down the stolen books.

“They almost never touched the New York Public Library because the security they had there was so great, and the security everywhere else was so terrible,” McDade said. “So they didn’t need to target the New York Public Library; they could just focus on the smaller ones.”

Whether it was out of hubris or an ambition to take down the ultimate score, one of the criminals eventually had the temerity to steal from the New York Public Library, taking first editions of “Moby-Dick,” “The Scarlet Letter” and an extremely rare book of poetry by Edgar Allan Poe.

But that was the beginning of the end of the book ring, because it put the determined Bergquist on their trail.

“Before they stole from the New York Public Library, Bergquist was only moderately interested in the book-theft ring,” McDade said. “But once they stole from his collection, it became almost a quest for him to put these guys out of business and get the books back. It was a personal affront.”

And the way Bergquist did that was tied to his personality, McDade said.

“Bergquist was a gregarious guy who would talk to anyone – he would talk to book scouts and booksellers and librarians, and his whole idea was whenever he caught someone stealing, he would get the goods back and then immediately try to turn them to the good side,” he said. “He thought everyone was redeemable; he didn’t want anyone going to jail. He wanted them to repent and stop stealing, and then come back to the library side of things.”

One of the thieves eventually became an investigator for the Newark Public Library, but most of the other criminals just went to jail, McDade said.

For book lovers, the story has a bittersweet ending – the ultra-rare Poe book was eventually recovered but “The Scarlet Letter” and “Moby-Dick” were never found.

“With ‘Moby-Dick,’ it was a valuable item that would be difficult, but not impossible, to fence,” McDade said. “But for something like the Poe book, which was very, very rare, everyone who would be in the market for a title like that would know where every copy is coming from. That was the only advantage the New York Public Library had, so they contacted the people in the know, so that if that Poe book was sold somewhere in Manhattan, Philadelphia or Boston, they would get word.”

Even with consumers increasingly buying books electronically, rare-book theft is an omnipresent issue for libraries and museums, McDade said.

“I think books as artifacts are only going to continue to appreciate in value – maybe because of the move to e-books, maybe because of nostalgia,” he said. “But libraries have gotten more sophisticated when it comes to preventing book theft.”

So while it’s becoming harder and harder for outsiders to steal rare books from libraries, it’s the stealing of old maps, lithographs or archival sources such as letters that’s becoming problematic, McDade said.

“That’s really a growth area,” he said. “Think about how much a letter from Abraham Lincoln would fetch on the open market today. Actually, any letter from the Civil War-era written by anyone has some value.”

And the reason is because those items are much more accessible than the rare books, McDade said.

“None of those things individually are worth a mint, but if you steal enough of them, it can add up,” he said. “So there’s this wholesale looting of archives going on right now, and has been for the past decade or so. Most of these things are not catalogued at the item level, so it is sometimes impossible to know at all if they’re missing.”

According to McDade, the tragedy about the theft of archived materials is that those things are absolutely one-of-a-kind.

“So not only is the object gone, the information contained within it is gone, too,” he said. “Sometimes that information is mundane, but often it tells us something. Individual letters are important, because that’s the stuff with which history is written.”

McDade also is the author of “The Book Thief: The True Crimes of Daniel Spiegelman.” He teaches legal research at the College of Law and a class called “Rare Books, Crime & Punishment” in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science.

To contact Travis McDade, call 217-244-1640; email mcdade@illinois.edu

[Top]