Source: By Todd Leopold, CNN

Updated 8:31 PM ET, Fri February 19, 2016

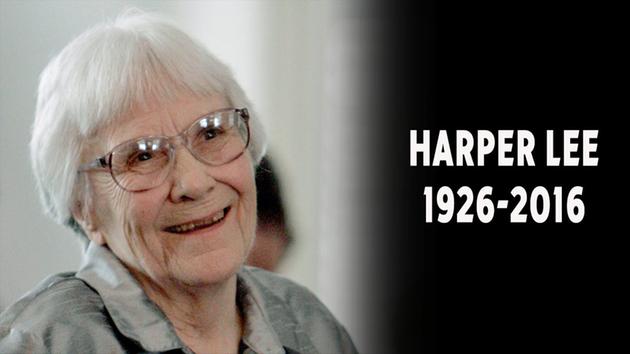

(CNN) Harper Lee, whose debut novel, "To Kill a Mockingbird," immortalized her name with its story of justice and race in a small Southern town and became a classic of American literature, has died. She was 89.

Her death was confirmed Friday by the City Hall in Monroeville, Alabama, where she lived.

In a statement, Lee's family said, "The family of Nelle Harper Lee, of Monroeville, Alabama, announced today, with great sadness, that Ms. Lee passed away in her sleep early this morning. Her passing was unexpected. She remained in good basic health until her passing. The family is in mourning and there will be a private funeral service in the upcoming days, as she had requested."

Added nephew Hank Conner in the statement, "This is a sad day for our family. America and the world knew Harper Lee as one of the last century's most beloved authors. We knew her as Nelle Harper Lee, a loving member of our family, a devoted friend to the many good people who touched her life, and a generous soul in our community and our state. We will miss her dearly."

Her publisher, HarperCollins, also released a statement. "The world knows Harper Lee was a brilliant writer but what many don't know is that she was an extraordinary woman of great joyfulness, humility and kindness," said the company's president and publisher, Michael Morrison. "She lived her life the way she wanted to - in private - surrounded by books and the people who loved her. I will always cherish the time I spent with her."

"Mockingbird," which was published in 1960, was drawn from elements of Lee's childhood in Monroeville. In steady prose shaded by memory and lyricism, she describes how an impulsive girl, Scout Finch, her older brother, Jem, their friend Dill and a variety of other townspeople get caught up in the case of Tom Robinson, a black man who's been accused of rape in the Depression-era town of Maycomb, Alabama.

Through it all, no character is more indelible than that of Scout's widower father, Atticus Finch. The scrupulous, fair-minded lawyer who defends the falsely accused Robinson in a racist courtroom set a standard for goodness and bravery that still resonates more than 50 years later.

"I wanted you to see what real courage is, instead of getting the idea that courage is a man with a gun in his hand," Atticus says to Scout at one point. "It's when you know you're licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see through it no matter what."

The book won the Pulitzer Prize, and Gregory Peck, who played Atticus in the acclaimed 1962 movie, earned an Oscar for best actor. Finch was named the greatest hero in movie history in a 2003 American Film Institute survey. His reputation is such that a 2010 poll by the American Bar Association Journal was titled "The 25 Greatest Fictional Lawyers (Who Are Not Atticus Finch)."

An earlier draft of the book, titled "Go Set a Watchman," was published in 2015. The book was criticized for a different portrayal of Atticus, who voices racist sentiments, and questions arose as to whether Lee actually wanted it released.

Despite mixed reviews, the book was one of the top sellers of 2015.

Throughout all this, Lee maintained a low profile. She had assisted her friend Truman Capote, the basis for Dill, while he researched his novel "In Cold Blood," and though he reveled in the praise and fortune that came with fame, she resisted it.

"I never expected any sort of success with 'Mockingbird,'" she told critic Roy Newquist for an interview published in 1964. "I didn't expect the book to sell in the first place. I was hoping for a quick and merciful death at the hands of reviewers, but at the same time I sort of hoped that maybe someone would like it enough to give me encouragement. Public encouragement. I hoped for a little, as I said, but I got rather a whole lot, and in some ways this was just about as frightening as the quick, merciful death I'd expected."

Even as "Mockingbird" became a fixture on high school reading lists and demands for her became ever more pronounced, she took shelter in New York and Alabama, hiding in plain sight. It wasn't that she was reclusive, exactly; it's that she preferred to let her work speak for itself.

At one event in her honor -- and there were many -- she was asked to address the audience at the Alabama Academy of Honor. She turned down the opportunity.

"Well, it's better to be silent than be a fool," she said.

'I kept at it'

Nelle Harper Lee was born in Monroeville on April 28, 1926. She was the youngest of five children born to Amasa Coleman (A.C.) Lee and Frances Cunningham Finch. Though A.C. was not a widower like Atticus, Lee's mother was mentally ill, so she and her siblings were essentially raised by her father. The two became very close.

She met Truman Persons, who was two years older, as a child. The tomboyish Lee and the sometimes petulant Persons, who was sent away by his parents to spend his summers in Monroeville, became close friends and would spend hours reading and making up stories. Recognizing his daughter's imaginative temperament, A.C. Lee gave her an Underwood typewriter. She carried it everywhere.

Lee attended the University of Alabama, including a short stint in law school, but didn't finish. Instead, she moved to New York where Truman Persons, now Truman Capote, had established himself as one of the country's leading writers.

Lee, too, wanted to write but had little time to pursue the vocation until a pair of Capote's friends, Michael and Joy Brown, gave her a Christmas gift: They would pay all her expenses for a year. Lee took two to write "To Kill a Mockingbird."

Though the book seems effortless, she told Newquist it came in stops and starts.

"Naturally, you don't sit down in 'white hot inspiration' and write with a burning flame in front of you," she said. "But since I knew I could never be happy being anything but a writer, and 'Mockingbird' put itself together for me so accommodatingly, I kept at it because I knew it had to be my first novel, for better or for worse."

After she finished "Mockingbird," Capote -- fresh off the success of "Breakfast at Tiffany's" -- invited her to assist him on a new project: the story of a murdered Kansas family, the Clutters. Lee became part secretary, part interviewer, part go-between for the flamboyant Capote. The work they did would become the foundation of Capote's 1966 best-seller, "In Cold Blood."

"Mockingbird" was published in July 1960 and became an immediate best-seller. Indeed, it's never stopped selling; as of 2006, it had sold 30 million copies and moves a million more each year.

Lee was caught off guard by its success.

"I can't say that (my reaction) was one of surprise. It was one of sheer numbness. It was like being hit over the head and knocked cold," she told Newquist.

Book to screen

The book won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and was optioned for a movie. Lee was wary of Hollywood's attention but was allowed some input. Her choice for Atticus was Spencer Tracy, but he was unavailable. The studio's first choice was Rock Hudson.

When Gregory Peck was chosen, he traveled to Monroeville to meet with Lee. He became so attuned to the role that Lee burst into tears the first time she saw him in character. The two became lifelong friends. After filming concluded, Lee gave the actor her father's prized pocket watch; later, Peck's grandson was named for the author.

The movie has been called "the best-ever book-to-screen adaptation." It captured Lee's world just right: the dilapidated homes, the county courthouse (built on a backlot but based on the actual Monroeville building) and, above all, her characters.

The performers who played Scout and Jem, Mary Badham and Philip Alford, were Alabama-born acting novices. Brock Peters, who played Tom Robinson, broke away from the heavies he'd portrayed before landing the role. (More than five decades later, he would deliver the eulogy at Peck's funeral.) Robert Duvall, who played the mysterious Boo Radley, was a screen newcomer. He would go on to a storied career.

With the success of the film, "To Kill a Mockingbird's" place in the culture was cemented. But Lee never followed up. She worked on a second novel but never finished it. Later she tried her hand at a true-crime book. That, too, would remain incomplete.

"Go Set a Watchman" was an earlier version of "Mockingbird." The book engendered its share of controversy over concerns that Lee, by then in an assisted-living facility, hadn't approved its release, despite a statement that she was "humbled and amazed that this will now be published."

Regardless, "Mockingbird" was a career in itself.

The story was both a steady source of income and, eventually, somewhat of a millstone for Lee. She spent many years sharing a house in Monroeville with her sister, Alice, a centenarian who followed in her father's footsteps as a lawyer. Strangers would knock on the door and ask for autographs. Lee sued a local museum over trademark infringement. She got caught up in a lawsuit in which she claimed she was "duped" into signing over the copyright to her book. The suit was settled in 2013.

Over the years, biographers and reporters would attempt to get close to Lee. For the most part, she resisted their blandishments, though one teacher, Charles Shields, wrote a 2006 biography, and a Midwestern journalist, Marja Mills, moved next door and eventually wrote a book, "The Mockingbird Next Door" (2014). By then, Harper Lee had suffered a stroke and both Lees needed more detailed care.

Nevertheless, there is no forgetting "Mockingbird." The film lives on; it's in the National Film Registry. Each year, Monroeville puts on a staged version of the story.

And, of course, there is the book, still selling, still being read, still moving many to tears.

The book, and its author, offer two qualities that are often in short supply: respect and restraint.

Perhaps there is no more moving example than a famous scene from the book and movie. Atticus Finch has just lost the rape trial. His client, Tom Robinson, will probably be put to death. In the balcony, Scout and Jem sit with Maycomb's black community in stunned silence. As Atticus quietly leaves the courtroom, the Reverend Sykes, a local black leader, gets Scout's attention. The citizens on the balcony are all standing. He urges her to do the same. "Miss Jean Louise," he says, "stand up. Your father's passin'."

Lee never married and had no children.

[Top]