Theodore Low De Vinne - American printer and author on typography

Posted on February 20, 2014 inAuthors, Book Memories, Collectors of Note, Education, Uncategorized

Source: Wikipedia

Theodore Low De Vinne (December 25, 1828 – February 16, 1914) was an American printer and scholarly author on typography. De Vinne did much for the improvement of American printing.

Contents

Life and career

Theodore L. De Vinne was born at Stamford, Connecticut, and educated in the common schools of the various towns where his father had pastorates. He developed the ability to be a printer while employed in a shop at Fishkill, New York. He worked at the Newburgh, New York Gazette, then moved to New York City. In 1849 he entered the establishment of Francis Hart, and worked there until 1883 when the business was renamed Theodore L. Devinne & Co. In 1886 he moved to a model plant designed by him on Lafayette Place, which still stands.

De Vinne either commissioned Linn Boyd Benton, or co-designed in conjunction with Benton, the hugely popular Century Roman typeface for use by The Century Magazine, which his firm printed. For use at his own press, he also commissioned Linotype to produce De Vinne, an updated Elzevir (or French Oldstyle) type, and the Bruce Typefoundry to produce Renner, a Venetian face. However, his biographer Irene Tichenor notes that De Vinne's private correspondence shows he was not closely involved with the design of "De Vinne" and he ultimately was somewhat unhappy with the type.

He was one of nine men who founded the Grolier Club, and he was printer to the Club for the first two decades of its existence. He was also a founder and the first president of the United Typothetae of America, a predecessor of the Printing Industries of America.

Works

A prolific author in the periodical printing trade press, De Vinne was also responsible for a number of books on the history and practice of printing. For years his publications ranked at the head of American presswork. His works include:

- The Invention of Printing (1876)

- An investigation of the claims of Laurens Coster to be inventor of printing with movable type, and awarding the honor to Gutenberg

- Historic Printing Types (1886)

- Plain Printing Types (1900) (The Practice of Typography, v.1)

- Correct Composition (1901) (The Practice of Typography, v. 2)

- A Treatise on Title-Pages (1902) (The Practice of Typography, v.3)

- A revision of his earlier Title Pages as seen by a Printer, published by the Grolier Club in 1901

- Modern Methods of Book Composition (1904) (The Practice of Typography, v.4)

- Notable Printers of Italy during the Fifteenth Century (1910)

See also

References

- Jump up ^ Irene Tichenor, No Craft without Art: The Life of Theodore Low De Vinne. (Boston: David R. Godine, 2002), pp. 106-109. ISBN 1567922864

- Jump up ^ Mac MacGrew, "American Metal Typefaces of the Twentieth Century, Oak Knoll Books, New Castle Delaware, 1993. ISBN 0938768344

- Jump up ^ Tichenor, No Craft without Art, pp. 125-126.

Stephen Hawking, Arthur C. Clarke and Carl Sagan discuss the Big Bang theory, God, our existence

Posted on January 20, 2014 inAuthors, Education, Uncategorized, Video

Stephen Hawking, Arthur C. Clarke and Carl Sagan discuss the Big Bang theory, God, our existence

Some of these men are no longer with us. This remarkable interview was accomplished with video connections from several sites.

All three of these men are genius, scientists and authors. I found this interview quite interesting and hope you enjoy it as well.

[Top]On Today's Date 1843 Charles Dickens A Christmas Carol Was Published

Posted on December 18, 2013 inAuthors, Book Memories, Book News, Uncategorized

1843 – A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (pictured), a novella about the miser Ebenezer Scrooge and his conversion after being visited by three Christmas ghosts, was first published.

[Top]Doris Lessing

Posted on November 20, 2013 inAuthors

Doris Lessing 2007 - 18 November 2013

It is with great sadness that we bid farewell to the Nobel Prize winning author and Booktrust President Doris Lessing, who died aged 94 this weekend.

She was a brave novelist, who made an immense contribution to the literary world, and we are forever grateful for the support she gave us in encouraging reading and writing.

Lessing completed more than 50 novels during her lifetime, spanning a broad spectrum of politics, science and feminism. Her longest and best-known work, The Golden Notebook, explored the layers of one woman's personality, leading her to become a trailblazer of the feminist movement. She, however, felt that her 1970s science fiction series, Canopus in Argus, was her best work.

I read because I adored it, and still do. Born in Iran and raised in Zimbabwe (issues of post-colonial politics were very present in her novels), Lessing dropped out of school at 13, and took to ordering parcels of books from England. From Dickens and Kipling, she fed her imagination, and was soon making up bedtime stories for her brother - they provided her with an escape. When she appeared on Desert Island Discs in 1994 she was asked if she read as a child out of boredom, to which she responded 'No, I read because I adored it, and still do'.

She was heavily decorated with awards and prizes, including the David Cohen Prize in 2001, which is now one of Booktrust's portfolio of managed prizes. In 2007, she arrived at her North London home to find a sea of reporters and photographers on her doorstep, following the announcement of her as as the oldest person to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. In typical Lessing fashion, she was unimpressed by the intrusion, encumbered as she was with heavy shopping bags, and merely offered the words 'Oh Christ!' to reporters!

[Top]This is Not the End of the Book: A Conversation

Posted on July 16, 2011 inAuthors, Book Collecting, Book News, Collectors of Note

Source: NationalPost.com by Philip Marchand

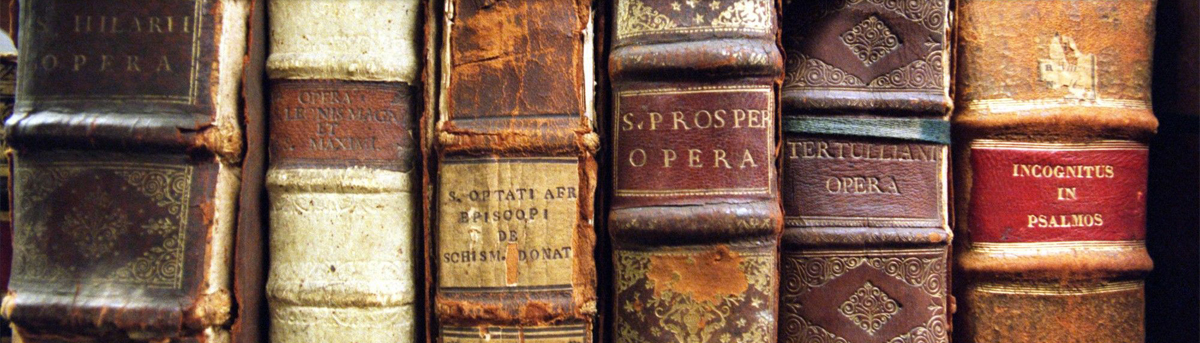

Fear not, bookworms and library rats. Two fellow bibliophiles, novelist (The Name of the Rose) and critic Umberto Eco, and playwright and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere, have collaborated on a volume whose title says it all: This is Not the End of the Book: A Conversation Curated by Jean-Philippe de Tonnac.

Eco lays out his argument very early in this “conversation.” (Don’t ask me what “curated” means.) “There is actually very little to say on the subject,” Eco states. “The Internet has returned us to the alphabet … From now on, everyone has to read. In order to read, you need a medium. This medium cannot simply be a computer screen.” The implication of Eco’s logic is clear. E-books have their place in the world of letters, but not necessarily one of total dominance. “One of two things will happen,” Eco continues in his march of logic. “Either the book will continue to be the medium for reading, or its replacement will resemble what the book has always been, even before the invention of the printing press. Alterations to the book-as-

object have modified neither its function nor its grammar for more than 500 years. The book is like the spoon, scissors, the hammer, the wheel. Once invented, it cannot be improved.”

Now that what little to say on the subject has been said, we can savour what this particular book is really about, the spectacle of two European intellectuals exchanging aperçus. Here are the fruits of a lifetime of reading, stockpiled and readily available to both speakers. At one point, Carriere directs our attention to forgotten French baroque poets. Eco responds with a reference to neglected Italian baroque poets. They move on.

What really drives the conversation, however, is the subject of their book collections. “Not counting my collection of legends and fairy tales, I own perhaps 2,000 ancient books, out of a total of 30,000 or 40,000,” Carriere says. “I have 50,000 books in my various homes,” Eco comments. “I also have 1,200 rare titles.” Both men maintain they are interested in previous owners of their books. “I love owning books that have belonged to others before me,” Carriere says. Eco concurs. “I own some books whose value comes not so much from their content or the rarity of the edition as from the traces left on them by an unknown reader, who has underlined the text, sometimes in different colours, or written notes in the margin.”

Eco’s collection is more focused than Carriere’s. It is a “collection dedicated to the occult and mistaken sciences.” It contains works, for example, by the misinformed astronomer Ptolemy but not by the rightly informed astronomer Galileo. “I am fascinated by error, by bad faith and idiocy,” Eco tells us. He loves the man who wrote a book about the dangers of toothpicks, and another author who produced a volume “about the value of being beaten with a stick, providing a list of famous artists and writers who had benefitted from this practice, from Boileau to Voltaire to Mozart.” He adores the hygienist who recommended, in his treatise, the practice of walking backwards. Eco does not tell us how many of these books he actually owns, or how much he would pay for a first edition in mint condition.

Eco and Carriere exchange insider information about book collecting. You can find the occasional bargain, Eco says. “In America, a book in Latin won’t interest the collectors even if it’s terribly rare, because they don’t read foreign languages, and definitely not Latin.” A Mark Twain first edition is what excites them. De Tonnac asks each man about his dream find. Eco’s response is conventional: “I’d like to dig up and keep, selfishly, a copy of the Gutenberg Bible, the first book ever printed,” he says. Carriere opts for the discovery of “an unknown Mayan codex.”

A more interesting question, posed by de Tonnac, is whether “an unknown masterpiece might still be discovered.” Eco’s response is similar to the comments of the late critic Hugh Kenner. Kenner pointed out that if a copy of the Iliad turned up for the first time today it would arouse an archeological curiosity but little more. Eco agrees. “A masterpiece isn’t a masterpiece until it is well known and has absorbed all the interpretations to which it has given rise, which in turn make it what it is,” he says. “An unknown masterpiece hasn’t had enough readers, or readings, or interpretations.” Shakespeare, in contrast, is getting richer all the time. Disagreeable though it is to admit this, the anti-Western canon agitators have a point — literary masterpieces don’t simply drop from the heavens, or emerge from the brain of an inspired individual. Fate and politics play their roles.

The conversation in this book is full of interesting and sometimes heartening tidbits. “We are living in the first era in any civilization to have so many bookshops, so many beautiful, light-filled bookshops to wander around in, flicking through books,” Eco assures us. It is also salutary to be reminded that the preservation of cultural memory is an ongoing, urgent task. We assume that the contents of libraries and archives are being digitized, for example, without loss of significant printed material. This is not so. Carriere says that a truck arrives at the National Archives in Paris every day, “to take away a heap of old papers that are to be thrown out.”

Of the two conversationalists, I prefer Eco. Carriere is a little bit too cozy with the eminent. “I sometimes visit second-hand bookshops with my friend, the wonderful author and well-known bookseller Gerard Oberle,” he will state, or he will refer to, “My friend, the great Brazilian collector Jose Mindlin,” or he will find occasion to recall scenes with his good friends Luis Buñuel or Jorge Luis Borges or Jean-Luc Godard. I know it is hard for a top drawer French intellectual to avoid this, and I may simply be jealous. But I also notice that when a banality or an outright piece of misinformation pops up, it always comes from Carriere. You would never have Eco stating, for example, that the Gnostic Gospel According to Thomas is “a verbatim account of the words of Jesus,” or repeating an even hoarier canard, that St. Paul was “the real inventor of Christianity.”

Still, Carriere helps Eco keep the conversational ball in the air and free from any taint of theoretical jargon. Three cheers for these two hardy veterans of the cultural industry.

[Top]