Rare Book School Program Celebrates the Embattled Book

By Daniel de Vise, Washington PostPublished: July 28

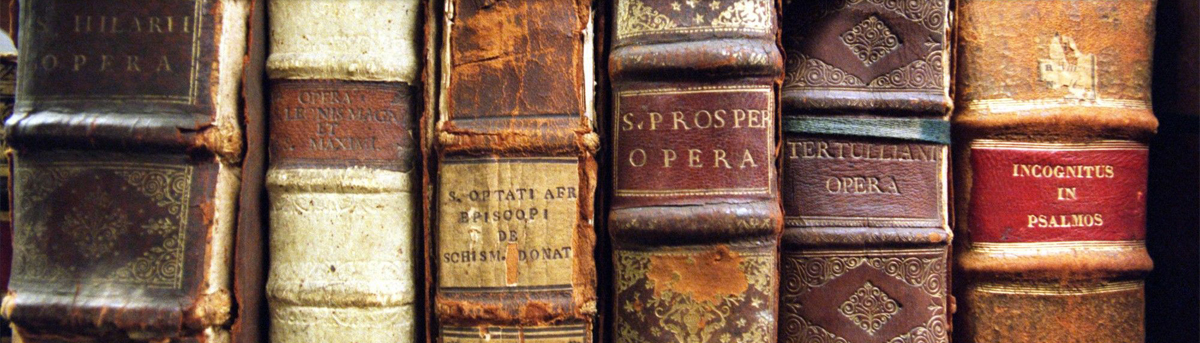

CHARLOTTESVILLE — Here is a book about handwriting by Palatino, a 16th-century calligrapher for whom a font is named. And here, a folio of Shakespeare’s plays that sold for one English pound in 1632. And here, an exquisitely illustrated, calfskin-bound Horace collection that bankrupted its publisher in 1733.

Welcome to Rare Book School, summer camp for bibliophiles. Tucked in the basement of the cavernous main library at the University of Virginia, the school is an annual five-week homage to the printed page. Or is it an elegy?

The modern book, a bunch of sheets bound together within a cover, has endured for two millennia, surviving the Dark Ages, radio, television and the moving picture.

But now it is threatened by an electronic version of itself. The e-book is projected to outsell the printed book by 2015, according to Publishers Weekly magazine. Borders bookstores have begun liquidation sales. Google intends to scan all the world’s books by the end of the decade.

And now there is a new urgency at Rare Book School, arguably the preeminent center for study of the book as artifact.

Founded at Columbia University in 1983, Rare Book School relocated to Charlottesville in 1992 as a nonprofit affiliate of U-Va. and found a niche as a place for librarians and scholars to decode the story told by the book itself: the ink, the paper, the typeface, the binding, the illustrations, the subtle notations in the margins.

“You have to teach people how to read the object, not just how to read the book,” said Michael Suarez, a Jesuit priest and English literature scholar who left a post at Oxford to run the school two years ago.

Bookbinding and publishing lore once were the province of library schools. But they strayed from that mission over the decades, Suarez said, to follow the gradual migration of information from printed pages to electronic screens. Some have dropped the word “library” from their names.

Rare Book School has gone in the opposite direction, amassing a collection of 80,000 items that range from 7th-century papyrus fragments to manuscripts stored on Reagan-era floppy disks and unreadable on the modern computer.

Unlike most special collections, this one is meant to be handled. Many items are ragged specimens of rare texts — worthless to the collector but priceless to the rare-book student — or multiple copies of comparatively obscure works, enough for every student. For the sake of the books, students are forbidden to enter a classroom with food, drink or pen; notes are taken in pencil.

One bookcase is given over entirely to Harry Castlemon’s Gunboat series, popular juvenile literature from the 1860s that time has forgotten, a collection assembled to illustrate the evolution of publishing in the 19th century. Another case brims with Baedeker’s travel guides, popular with tourists of the early 1900s. And surely no library has more copies of “The Tent on the Beach,” a specimen from the later 1800s that is a minor work of Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier.

Every corridor on the basement campus hums with adoration of the printed book, one of the more successful contrivances of the civilized world: compact and portable, with pages perfectly suited to opposable thumbs and a spine that fits neatly between the knees.

The codex, as the form is known, emerged in the early Christian era, said Amanda Nelson, the school’s program director. “I don’t see how we’re going very far from this,” she said, holding a tome in her hands, “because this is so perfect.”

The school offers 25 weeklong courses every summer, five a week from June through July. Last week’s crop of students included a bookshop owner from Washington state, an English graduate student from New Zealand, a historian for the Mormon Church, a school librarian from Long Beach, Calif., and collegiate librarians from Oxford and Yale.

Six hours of classes each day give way to wine-and-cheese receptions or evening lectures, prompting much worshipful talk of books.

“I riffle the pages with my thumb as I’m reading, and I can’t do that on a Kindle,” Jeremy Dibbell, a young staffer at Rare Books School, said one evening while dining with other staff and faculty.

“I think about getting an iPad, but not for books,” said Michael Winship, an English professor from the University of Texas who teaches during the summer in Charlottesville. He is considered an authority on 19th-century American publishing and teaches “The American Book in the Industrial Era, 1820-1940.”

Albert Derolez, teaching “Introduction to Western Codicology,” is a Belgian scholar who excels in Gothic manuscripts.

Martin Antonetti, teaching “The Printed Book in the West to 1800,” was once librarian of the Grolier Club, the nation’s premier organization for bibliophiles.

“You know the phrase, ‘So-and-so wrote the book on X?’ ” said Elizabeth Ott, a U-Va. doctoral student who works at the school. “That’s often literally the case with Rare Book School professors.”

In class, students take turns operating wooden and iron printing presses and hanging pages to dry. Or they gather round ancient manuscripts for a closer look at this goatskin binding or that woodblock rendering.

Antonetti opens printer Johannes Pine’s 1733 edition of what is known as Pine’s Horace. With engraved copper plates, it was a luxury buy for the 18th-century European aristocrat.

“Pine engraved it and published it and went bankrupt,” Antonetti said. “He published a Pine’s Virgil to recoup his losses, but that was the final nail in his coffin.”

Terry Belanger, an English literature scholar, started Rare Book School as a laboratory on the history of books and printing within Columbia University’s School of Library Service. Over time, the school gained a reputation as a world leader in training librarians and scholars to collect, catalogue and preserve rare books.

With the future of the book itself now in question, the school’s mission seems all the more clear.

“I actually think that the digital is making us much more aware of the form of the printed book. And so I think this is a moment of rare opportunity, rather than a moment of great crisis,” said Suarez, who co-edited the million-word Oxford Companion to the Book. “This whole Gutenberg elegy, death-of-the-book thing — I’m not buying it.”

Link to this page

Link to this page